April Carlson

Share:

What’s old is new again.

St. Paul’s only major art museum reopened in early December in a bigger, better, brand-new space in the 1890s-era Pioneer Endicott building. The Minnesota Museum of American Art—affectionately dubbed The M—had been at risk of closing permanently only a few years ago.

Now it’s back and brimming over with art and visitors.

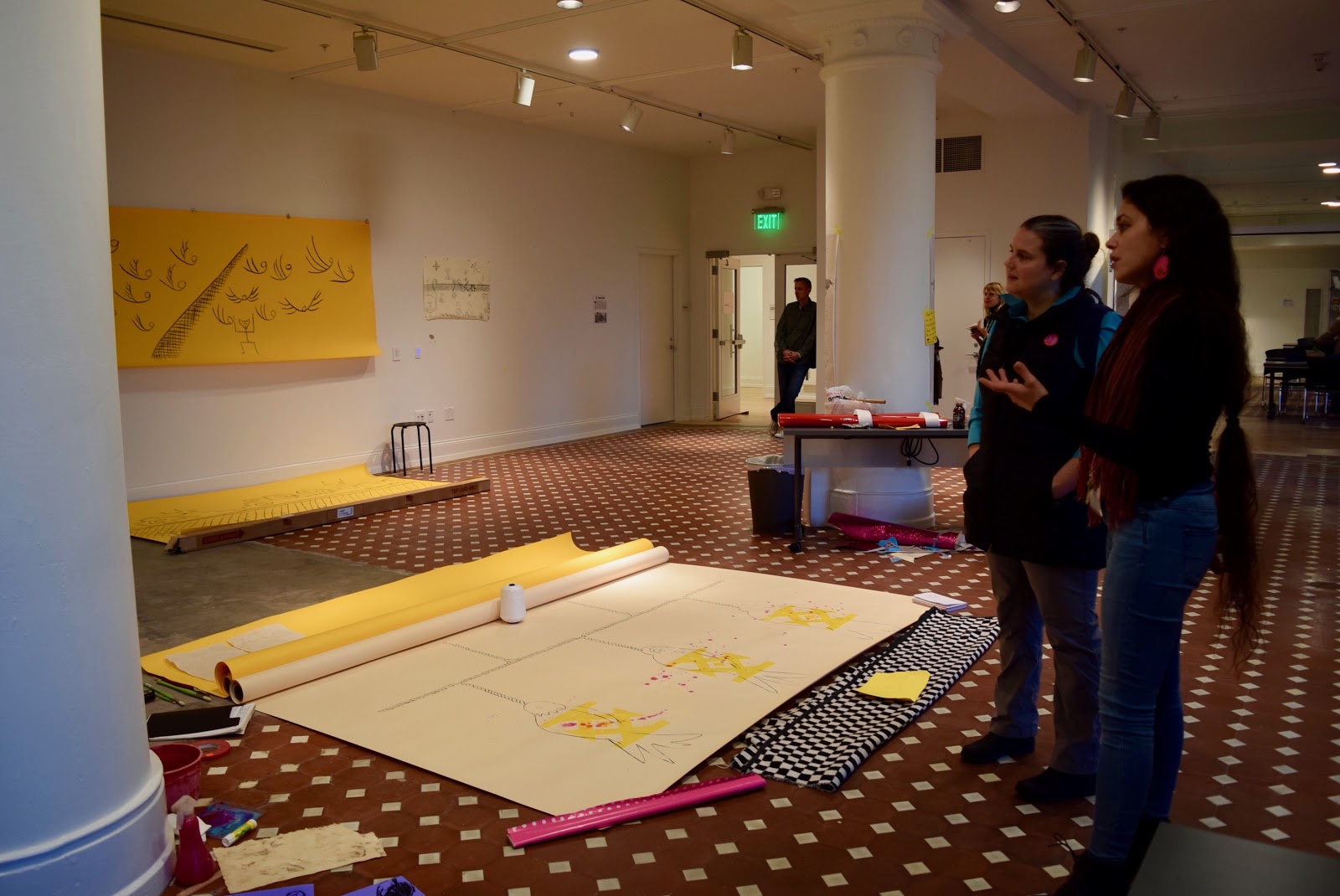

Guiding more than 40 art enthusiasts through the new location on Saturday, Dec. 15 was Metro State community faculty member G.E. Patterson. He is a poet, critic and teacher of creative writing.

Along with curator Christopher Atkins, Patterson led a tour and discussion with Minnesota artists David Bowen and Teo Nguyen. The free event was billed as “Conversation: (Un)Natural Landscapes.”

Bowen, a Duluth-based sculptor, brought the tour group to see Waveline, his conceptual, electronic sculpture displayed in The M’s Window Gallery.

Waveline is visible to passersby on the streets of downtown St. Paul. It consists of live video feeds of two coastlines on opposite ends of the globe.

The left two LED panels, which meet each other at a 90-degree angle, show a grainy, undulating image of where the Atlantic Ocean meets a shoreline in Puerto Rico.

The right two panels, also positioned at a 90-degree angle, display nothing at all—just two blank screens with a tangle of rainbow-hued wires beneath them. Was that due to some technical glitch?

The nothingness was no glitch, the artist explained. “[You’re looking at nothing right now because] it’s completely dark.” The right panels were showing a live feed of the Indian Ocean, from off the coast of Bali in Southeast Asia.

“Every once in a while, you might catch a squid fisherman or a fishing boat out there, but it’s very serendipitous,” Bowen said. “And if you stand out here long enough, you’ll eventually see the sun rise on the opposite side of the world.”

“This is like an elaborate clock, in a lot of ways,” he added. “You have to be patient. You have to check back in, because it’s always changing.”

The piece includes over 7,000 LEDs, which together emit ultra-low-resolution images. It is less like HDTV; more like watching a moving Monet painting.

“That is very intentional,” Bowen said. “In a way, [the lack of clear resolution] conveys the distance that exists between us and these shores.”

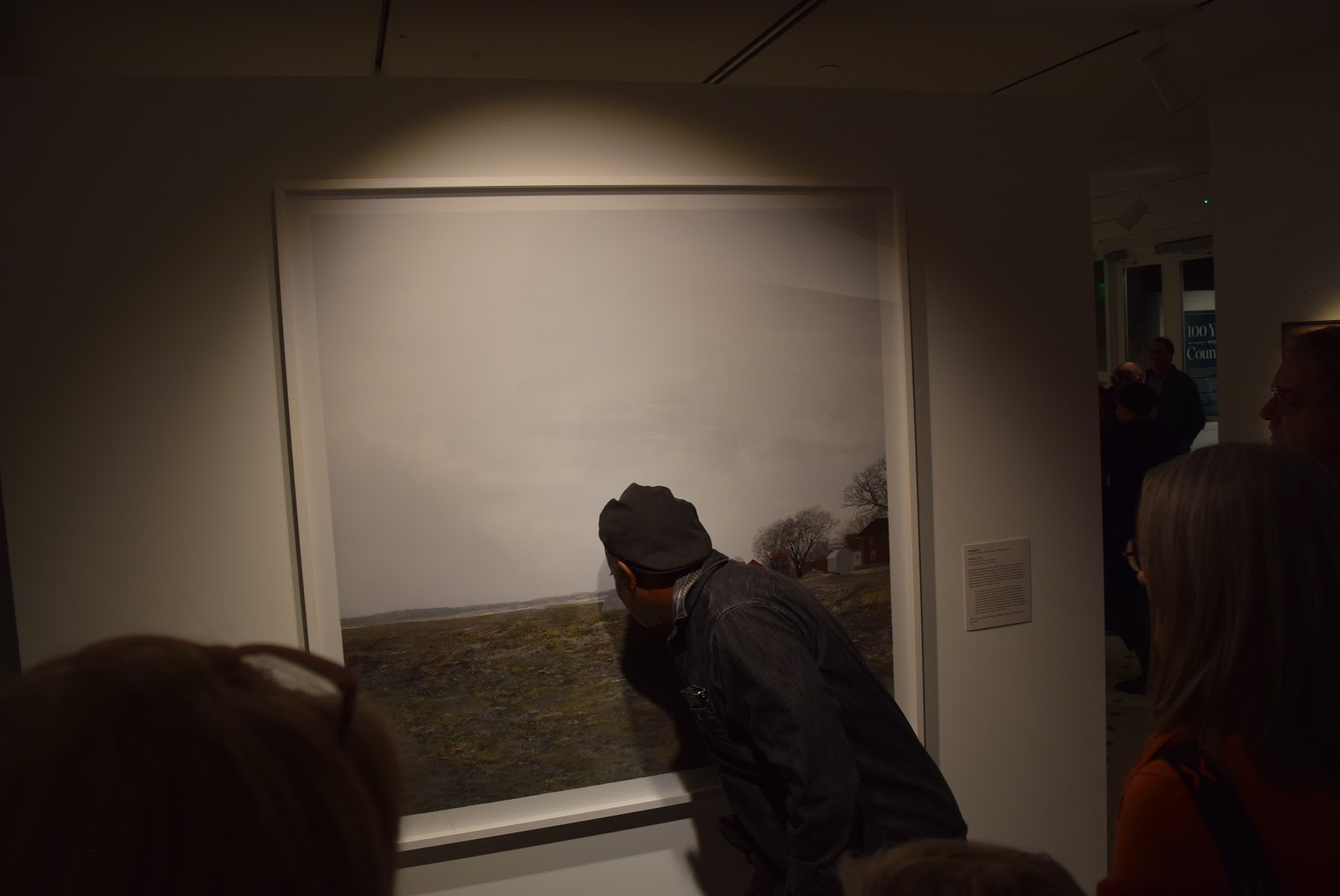

Back inside The M’s “100 years and Counting” gallery, Nguyen directed visitors to his large work on vellum, “Untitled I.”

Although Nguyen’s medium and subject matter are entirely different from Bowen’s, his landscape also seems to subtly glow.

Visitors unfamiliar with the artist were surprised to learn that “Untitled I” is not a giant photograph.

Instead, Nguyen used many layers of thin acrylic paint to create an incredibly realistic farmstead scene, recognizable to anyone familiar with rural Minnesota or South Dakota.

The painting is two-thirds winter sky—not wholly gray or blue or white, but somehow all and none of these colors. The horizon is the dominant presence in Nguyen’s work, and as with Bowen’s indistinct video feeds, that effect is very intentional.

Nguyen was born and raised in Vietnam and immigrated to the U.S. at age 16 with his family. They lived in California for a time, then made a cross-country drive to resettle in the Midwest.

“I was so in awe of these landscapes; it was completely new to me,” he said. “In Vietnam it is very mountainous, but here it is very flat. And there is something about that openness and flatness that is very beautiful and mesmerizing to me.”

“Vietnam is a war-torn country, and so this peacefulness [of the Midwest] really speaks to me,” Nguyen explained. “There is something almost romantic about [this landscape]. Maybe this is something I long for, for my own people.”

Patterson added his perspective on landscape and place during this conversation with Nguyen.

“I’m part of a collection of four centuries of African American nature poetry,” Patterson said. “What’s so striking, to me as an outsider—as Teo was suggesting—is often not what’s striking to the people who are longer-time residents.”

Patterson then invited the attendees to share their thoughts on landscape. One audience member wondered about the thematic similarity of horizon in both Bowen’s and Nguyen’s work.

“Horizon is often used in visual art to distort the emotions and disorient the viewer,” replied Patterson. “It’s about quietness, restfulness, but also about the embrace.”

“These emotions, combined with melancholy and anxieties around climate change, are all terrifically and interestingly balanced,” he said.

Gayle Cole, another audience member, told Nguyen that the dominant sky in his painting made her feel far away—but the care and fine detail he put into the farm buildings drew her nearer.

“For me, I have always been an observer my entire life,” Nguyen said. “Being an immigrant here, I am constantly observing [from the outside]. So I am able to appreciate some of these small things that Midwesterners might overlook.”

At the close of the conversation, Patterson thanked the artists for sharing their time and talent. He offered a parting quote from impressionist painter Claude Monet: “A landscape does not exist in its own right, since its appearance changes at every moment. But the surrounding atmosphere brings it to life. The light and the air which vary continually.”

Gesturing to the art and artists, Patterson added: “There is a kind of mutability in both of these works. And an intense looking, or recording, that captures that [idea] and makes the experience feel real for the people who view them.”

Photo by Margot Barry

The M—Minnesota Museum of American Art

Located in the historic Pioneer Endicott

350 Robert Street North, St. Paul, Minnesota

Monday – Closed

Tuesday – Closed

Wednesday – 11 a.m. – 5 p.m.

Thursday – 11 a.m. – 8 p.m.

Friday – 11 a.m. – 5 p.m.

Saturday – 11 a.m. – 5 p.m.

Sunday – 11 a.m. – 5 p.m.

“Flash Talks” are free and open to the public, beginning March 8

Fridays and Saturdays at noon