How To Halt The Decline Of The Found Footage Genre And Rediscover Its Relevance Again

by Erik Suchy August 17 2020

(Noam Galai / Getty Images)

Moviegoers line up at nationwide theatre chains to experience a film that will bring the “found footage” movie genre into the mainstream. It’s the type of motion picture that appears to be shot from the view of a home camcorder, and may be presented as though it were raw footage. As such, it may introduce a disclaimer stating this. Supposedly, what the audience will see is the footage located at the last-known site of someone’s disappearance. For the sake of pacing, it has been edited together into a narrative format by the authorities who have discovered it.

As they stroll to their seats, arms full of popcorn, they ponder. Just how profound will the effectiveness of this movie’s new filmmaking technique settle on them? After all, Roger Ebert deemed it an “incredibly effective horror film,” while Peter Travers of the Rolling Stone called it “a groundbreaker in fright that reinvents scary for the new millennium.”

They wait in hushed anticipation as the lights dim. Then, the film starts.

80 minutes later, some will be shaking, perhaps crying in fright at what they witnessed on screen. Others may throw their hands up, confused as to what they saw.

But despite the mixed audiences reaction, what is certain is that the movie will inspire a generation of similar works, taking a significant amount of influence from its original source.

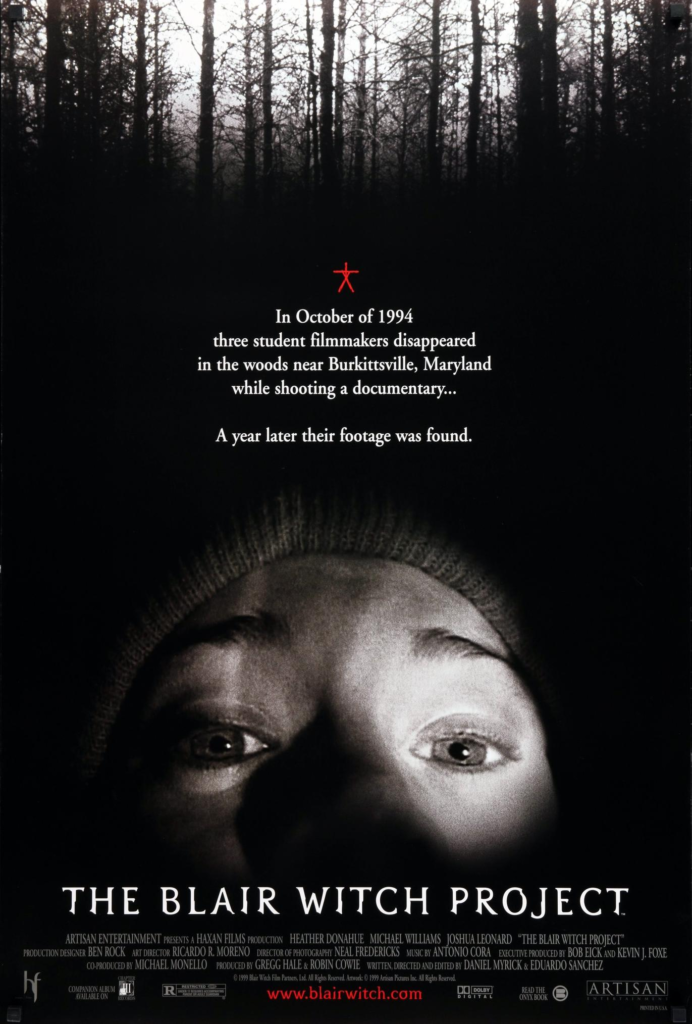

That film is none other than The Blair Witch Project.

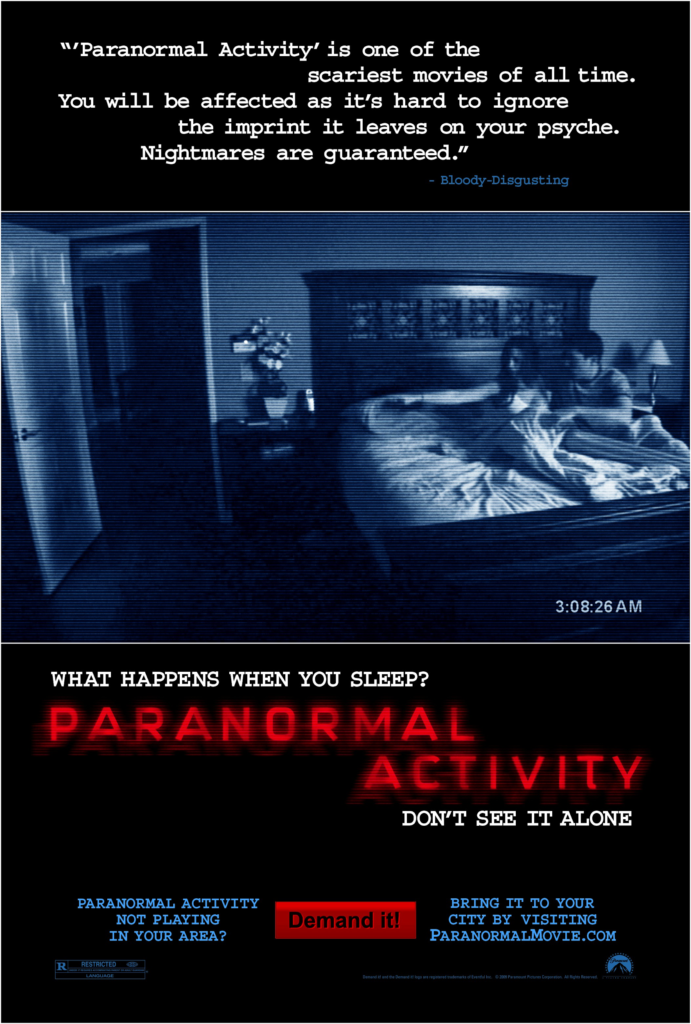

(Paramount Pictures / IMDB) (Haxan Films / IMDB) (Paramount Pictures / IMDB)

However, in the next two decades, the oversaturation of these types of movies that have flooded both mainstream theatre chains and home video releases have been unstable at best. They range from box office successes and critical cheers to scanty profits and negative reception.

Some films, such as Paranormal Activity, REC, and Cloverfield have managed to touch the hearts of some whose penchant for shaky-cam horror excels into the stratosphere. Others, such as The Devil Inside and The Gallows have been seen as nothing but a low-cost, derivative knock-off that fails to showcase a terrifying experience. And as the positive critical receptions continue to become sparse, one thing is for certain.

Audiences don’t seem to care for the found footage genre. And there doesn’t seem to be any indication it will be desired soon again.

But as an admirer of the genre myself, I believe that the sand in hourglass hasn’t gone away. I still believe there’s a chance for it to earn back the love it’s been waiting for.

And here is how one can do exactly that.

For starters, it makes all the sense to cast relatively unknown first-time “actors” to star in a found footage horror film, and have their on-camera counterparts keep their real-life names for the movie. The “genius” of this tactic, and how it worked to perfection in Blair Witch’s favor was that it gave the suggestion to the casual viewer that if the “footage” we were witnessing was real, surely the real actors/actresses who kept their names on camera must have actually vanished.

But by now, during the end credits, we’ve seen the good ol’ All Persons Fictitious Disclaimer, and many of us aren’t buying this anymore.

For a much-desired change, it’d be interesting to cast more renown A and B-list stars as the leads. To cast someone with a far more charismatic acting range would help suck the viewer into their character development, and would help sympathize with their plights much better. Even though the perception that any relation to actual characters now becomes obsolete from the film, one can also understand that the movie is trying to not take itself seriously by claiming what we are watching is actual footage recovered at the site of a “massacre” by authorities.

Additionally, the charisma that a star like Edward Norton or Michael Shannon can showcase is nothing short of phenomenal by Hollywood’s acting standards. It can easily outshine the more awful performances most first-timers display in their middle-of-the-road Paranormal Activity rip-off. Fictional passion portrayed in a work of, well, fiction can still be depicted as authentic in a film treating its subject matter as real.

Speaking of realism, a found footage film is only as real as the villain it presents, and seldom ever does it employ a different “evil” for our protagonists to combat. From bloodthirsty demons to mindless, flesh-devouring zombies, there’s always some type of sinister creature acting as the feature’s main antagonist.

Usually, what scares the audience in a theatre, or on their couch is the suspense from withholding the visual element of the creature’s appearance. As such, in the Blair Witch Project, the fear came from not knowing what the titular spirit was capable of, or what it looked like in a physical form. The same holds true for Paranormal Activity, Cloverfield, and other knock-offs and clones where the fear came from what we never saw. Or at least what the film built up to revealing.

Yet again, though, this is another movie trope that has been overdone since. Regardless of how little we see something, and no matter how terrifying it looks, we know its desire is to stalk and kill, and that’s it. But what if that “evil” never came from what we didn’t see physically? What if what scared us came from human nature, instead of a supernatural (or natural) beast’s nature?

After all, when we listen to the news, we tend to hear stories regarding acts of violence so sinister we wonder how a human being could do it. True, some of us may turn from listening to this. Some of us, however, may take up an interest in this. We examine and research what prompted someone of our own flesh and blood to carry it out, and what their motive was.

While the argument can be made that someone recording everything they encounter does shatter the element of realism to a degree, that can be forgiven if the movie tries to dive deeper into what motivates the character to film to begin with. What should be explored is the emotional or mental connection the cameraman has with his equipment. If the protagonist is a serial killer, do they film their crimes because of the sense of sick enjoyment it brings them to rewatch the way his victims suffer? This could leave a terrifying impression in the context of wondering how sick they could be from taping this, and if they’ll ever bring themselves to stop.

But even if one is willing to accept the premise that the footage is genuine, at some point they might begin wondering, “Why is that one guy filming everything with such an obnoxiously large camera on his shoulder? Don’t you think at some point he’d realize it’s more important to run away from whatever’s pursuing them and not try to always film it?” While the film’s screenplay may attempt to add some realism by having one character chastise said cameraman for this, it causes that illusion of reality to fade, as it seems unlikely that if pursued by something deadly, someone would want to capture it through the lens.

.

Instead, a mix of multiple different viewpoints via laptop webcams, security camera footage, and very occasional over-the-shoulder camera shots should be used. Rather than have someone who films everything for the sake of filming everything (otherwise there’d be no picture to see), having the action recorded through different cameras that the main character doesn’t have control over enables the film to become more genuine.

If someone were attempting to elude a flesh-craving monster, the natural human reaction would be to forgo getting an actual picture of said creature. To ensure that we the viewers, however, can still see what’s happening, it could be filmed via a chest cam, or even something miniature concealed in a pair of glasses. Within an instant, the viewer’s mindset would change from “Why is this guy trying to film a steady shot of a monster that’s trying to eat him?” to “Oh, okay, so the action’s being filmed through the body camera on the guy’s chest. Maybe he forgot to turn it off when he was testing it or something.” This can be played to the movie’s advantage perfectly.

With countless titles being rolled off conveyor belts by both mainstream and independent studios, it may be safe to say that the found footage genre may never vanish completely. But perhaps, that decline still has the potential to be reversed entirely, and can be reinvented and revitalized for generation upon generation of theatre goers to come.